- Home

- Karen Pullen

Cold Heart Page 11

Cold Heart Read online

Page 11

“Ursula!” I called. “Hi!”

She turned, then scowled when she saw me. “What happened to you?”

“Accident.” I stuck out my hand to the girl, curious to find out who she was. “I’m Stella.”

“Lauren,” the girl said. She shook my hand. She was perhaps twenty, slender, with a gangly grace.

“Stella’s grandmother teaches the painting class I was telling you about,” Ursula said to Lauren.

“You two look so much alike, you must be related,” I said.

They looked at each other. “Well, yes,” said Ursula, nodding firmly, “we’re related. Sorry we can’t chat.” She turned away, busied herself with paying, then wheeled her cart towards the store entrance.

I felt vaguely snubbed, realizing they didn’t want me prying into their relationship. Hmmm. Fern would know. I called her.

“Did you see Temple’s baby?” Fern asked.

“He’s perfect,” I said. “Very wiggly.”

“I can’t wait till she brings him home. Well, Paige and I have been playing. And guess what we found.”

“What?”

“Some mini-CDs you might want to listen to. The box was in Paige’s closet, but they’re not children’s recordings, Stella, they’re odd—just people talking. They sound like phone conversations.”

I couldn’t imagine a few poor recordings could help me, but I trusted Fern’s instincts. “Sure. I’ll come over. What are you playing them on?”

“Paige has a boom box. I put in new batteries.”

I waved my ID at the guard at the Silver Hills gate and a few minutes later parked in Temple’s driveway. Her car, a dark green Toyota minivan, sat in the driveway. I looked in the garage window—Kent’s burgundy SUV was still there. Had I seen it last night, screeching through the streets of Verwood? I didn’t know. In the dark, I couldn’t tell one of the boxy cars from another.

Fern opened the front door and waved. Paige stood beside her, clutching a fraying, much-loved stuffed dog. Their outfits made me laugh—both Fern and Paige wore negligees, several strands of beads, and crimson lipstick. “We’re being movie stars today.”

“Hollywood, watch out,” I said.

Fern studied my face and I could tell she didn’t like what she saw. “I’ll be right back after Paige goes down for a nap. The CDs are in the kitchen.” She picked up a bottle of milk and led Paige up the stairs.

There were five mini-CDs, each a Memorex eighty-minute disc labeled in green marker with a date—February 10, 16, 20, and March 4 and 9. It might take hours to listen to all of them. I’d have to take them with me. I waited until Fern came back downstairs.

“What happened?” she asked. “It can’t be chicken pox, you had that when you were four.”

I gave her a version of the midnight events at Emilie Soto’s office. I dreaded telling her about my brushes with violence—Fern feared the risks of my job even more than I did.

“Oh, honey!” Fern lost her winsome smile and, for a moment, looked her age. She put her arms around me and squeezed. “I hate that you’re hurt.”

“Very superficial injuries.” I smiled reassuringly. She didn’t need to know about the lump underneath my piled-up hair.

“And poor Emilie! Will she be all right?”

“She will.” Optimism was called for. I motioned to the handful of compact discs. “Which of these is useful?”

She shrugged. “Can’t tell. Paige’s dad singing and reading stories, then other voices just talking. They sound like phone conversations.”

“I’ll have to listen to all of them to see whether they’re helpful or not.”

I was pretending very hard that I should take the CDs and listen to them. With no reason to suspect they were related to a crime, I couldn’t get a search warrant. But they probably contained nothing useful, so who would care? If I found anything, Fern could ask Temple to give them to me, conveniently forgetting to mention I’d already heard them. I thought briefly about calling Anselmo to come and listen with me, because two heads are better than one. But he’d question the legality of my possessing them. I decided not to involve him until I knew more.

One more question for Fern. She knew everything. “Who’s the young woman hanging out with Ursula Budd? Named Lauren, looks like her daughter?”

“She is.” Fern pulled out her knitting, a square of powder-blue yarn. She was making a blanket for Temple’s baby. “Ursula gave her up for adoption at birth. The daughter’s twenty-one now and she got her birth certificate, sought out her birth mother. Lovely, isn’t she?”

“It’s a happy reunion then.”

Fern bound off the square and started another, this one green. “Ursula wasn’t sure how George would take it. But he’s been fine so far. Did you know they’ve been married eighteen years? I’ve never understood that, they’re different as two people can be.”

“Come on, Fern, any marriage is a mystery to you.”

“She’s so lively and interested in doing new things. He’s dull as a tree stump, just fixes cars and goes fishing.”

“Who can explain love?” I mused, thinking about all the feelings I wasted on Hogan.

It was a rhetorical question, but she chose to answer it. “You’re right, Stella. They are genuinely fond of each other. And they both dote on their boy, Phillip. He’s a handful. Even Emilie Soto would have her work cut out with that one.”

I couldn’t respond. Emilie’s near-fatal shooting had scared me more than I wanted to admit, even to Fern. But I swear Fern could read my mind. “You should talk about it, Stella. It wasn’t your fault.”

I wasn’t so sure. “I want to find whoever did it.”

Fern knew how much Dr. Soto had helped me—with her careful listening, cajoling, and humor—to talk about my mother, Grace. She’d told both of us that my grief would be lessened if the killer were found, that having someone to blame would crystallize my sadness into anger, then satisfaction once justice was served. Well, justice for Grace hadn’t happened. Yet.

Before I left, I held Fern close. She was strong, fearless, and all the family I had. I wanted to put her on a cruise ship until this case was over. “You’ll be careful, won’t you?” I asked her.

“Stella! You’re sweet to worry about me,” she said, planting a sticky kiss on my cheek.

I took the five CDs home. Mixed in with recordings for Paige—Temple reading a story, Kent singing nursery rhymes—were hours of phone conversations. I heard Lincoln Teller telling Clementine he’d pick up Sue after soccer practice, arranging a golf game, and talking to Clemmie’s chef about special events. Ursula Budd, Lincoln’s bookkeeper, argued with her husband, George, about money, about their son’s school problems. The restaurant’s office phone must have been bugged. By Kent Mercer? Why? And why had he burned the CDs?

Listening didn’t improve my mood or help my aching head, and the only way I could stay awake was to keep busy. It was as good a time as any to make a dent in my neglected home environment. Though kind to hide his thoughts after one glance, Anselmo must’ve been horrified. I picked up all my dirty laundry and started a load of wash, then ran the vacuum. Cleared the kitchen table—junk mail, dirty dishes, ATM receipts, and one dust-covered zucchini, a present from my gardening neighbor. I found the box with the cooking pots and made marinara sauce with red wine—a favorite recipe that calls for a glass for the pot and a glass for the cook. After two glasses and two bowls of spaghetti my head ceased throbbing. My mood, while not glowing rosy, flushed faintly.

It abruptly improved when I inserted the fifth CD and heard a brand-new set of phone conversations: Bryce Raintree’s rusty voice arranging sales of prescription drugs, drugs freely available from Wisteria Acres, the nursing home where he worked. I sent a silent “thank-you” to Fern for her discovery of the five mini-CDs. This last one made the preceding dull hours worth-while.

It sounded like Bryce was the source of the oxycodone I bought from Kent Mercer at Clemmie’s almost a week ago. Why did Merce

r bug Bryce’s phone? Was he blackmailing Bryce? How far would Wesley go to keep Bryce, his son, from prison?

Since Bryce’s phone had been bugged illegally, my hands were tied.

But Fredricks might have an idea or two. Surely, mentoring your undercover drug agent must include a discussion of inadmissible evidence. Surely, Fredricks wouldn’t be annoyed that I’d traded our delightful evenings together for a homicide investigation.

I picked up my phone and called him.

“What’s up?” he answered, shushing the background video-game noises from his two rowdy boys. Skipping the small talk, I summarized my Bryce pills-and-illegal-recordings dilemma.

“He’s not using scrips?” Fredricks asked.

“No.” I knew where he was heading. Bryce was very small potatoes. We couldn’t flip him, because he was a one-man show. There was no unethical pain clinic to shut down, no unscrupulous doctor writing reams of prescriptions.

Fredricks was chewing something crunchy. Cheetos, probably. He’d always kept a stash for us in the truck, claiming the orange dust on my fingers added to my disguise. “When are you coming back to the streets? Your work awaits. Evergreen needs you.”

“You’re changing the subject,” I said.

“There’s an ocean of gray between black and white. Is the kid salvageable?”

I thought about Bryce, suffering through his mother’s terminal illness, the trauma of his brother’s murder. Hurting under a thick veneer of muscle. “He’s salvageable.”

“Best not to involve me, actually.”

“So you’re saying . . . don’t pursue an arrest?”

“Think of the system resources you’d save. Lawyers, court time, body-cavity searches. You’ll think of something.” He rang off, claiming a stovetop emergency.

I pondered. Where could Bryce take his muscles, besides jail? Where would they tame his flowing locks and lazy ways, teach him skills and respect for authority?

The answer was obvious.

CHAPTER 17

Saturday morning

June Devon had been in Fern’s classes for years, but we’d never met. Her name had popped up all over this case. She was Fern’s friend, Nikki Truly’s aunt, Zoë Schubert’s sister-in-law. Everyone knew June except me. Time to pay her a visit.

I called her to ask if I could stop by. “Sure,” she told me. “I get up with the sun. Come on over.”

Like Silver Hills, the White Pines development where June lived fronted Two Springs Lake, but there the resemblance ended. White Pines homes were modest, not mansions; the trees loblolly pines, not Japanese maples; the driveways gravel, not paved. Septic tank requirements gave each house two or three acres, spreading the houses apart. June’s house had a new-looking handicapped ramp.

She was a robust woman in her mid-fifties with the erect posture of a dancer and graying brown hair pulled into a ponytail. A petite parrot with green, orange, and yellow feathers—“a conure,” June told me—perched on her shoulder, head tilted as it peered at me with black beady eyes. It cried a rusty screech, a startling sound June ignored. I told her I was investigating Kent Mercer’s murder.

“You’re Fern’s granddaughter, right? You have her sea-blue eyes.” She tactfully didn’t mention my scabby face. Her home was furnished with dark, gloomy antiques but the paintings were colorful—soft, near-abstract but recognizably birds, a subject she clearly loved.

A loud groan from a nearby room startled me.

“That’s Erwin, my husband. You know he had a stroke last month? He can’t talk. Come, meet him,” June said. “I hope you don’t mind if I keep working. Lots to do.”

I followed her into a bedroom, musty with sour smells. Erwin lay on his back, watching us through bleary brown eyes. He was a large, gaunt man with stiff gray hair combed back from an expressionless face. He would have looked less alarming if he’d had a shave recently.

“Morning, sweetheart!” June kissed Erwin’s brow. “Ready to rise and shine?” Erwin grasped her arm as she helped him into a wheelchair. She wheeled Erwin across the hall and into a bathroom, leaving the door open. “We had to add this whirlpool tub. Cost a fortune, but it was that or the nursing home, even more money we don’t have. The tub’s good for his circulation.” She turned on the tub’s jets and the floor vibrated. She seemed careless of her husband’s privacy as she stripped off his pajamas.

Uncomfortable watching, I stepped back into her kitchen. The bird hopped around, from the sink to the stove to an open drawer. It seemed to have the run of the place.

June joined me. She took out a box of oatmeal and measured some into a bowl. “Erwin has to have food he can swallow without choking. He barely chews.”

“It’s a lot of work for you,” I said. “Do you have help?”

“He has a speech therapist three times a week, and a physical therapist for walking. They say he’s getting better. I guess he is. He can walk a bit now. A neighbor comes by so I can get out. Ursula Budd, do you know her? She helps with the insurance stuff. I don’t mind the work. I’m angry because my husband is gone. That’s—” she jabbed her thumb at the bathroom “—a wasted shell.” She put the bowl of oatmeal into a microwave. “I’ll tell you the truth. I’m jealous of women with husbands who drive, mow the grass, feed themselves, for Christ’s sake. I’m even jealous of widows for their freedom. No nursing, doctors, watching the money hemorrhage away.” She stared at me as if to make sure I got the full picture, then disappeared into the bathroom for a few minutes. The bird hopped about the table. When I held out my finger, hoping it might hop on, it pecked me gently, like a warning not to get personal.

June wheeled a dampish Erwin up to the table and placed the oatmeal in front of him. The bird nibbled a raisin from his bowl. An unsanitary practice, but I wasn’t the health inspector.

“Ursula’s coming this morning. She’s a doll, isn’t she, Erwin?” As June spooned the oatmeal into his mouth, he tipped his head back, either in agreement or to make swallowing easier, I couldn’t tell which. “I’ll take a walk while she’s here. There’s a hawk down by the lake. I want to find its nest.” After a few bites, Erwin pressed his lips together, shook his head, so June gently washed his face. She wheeled him into the next room and helped him into a recliner in front of the TV, tuned to a kids’ channel.

She returned to the kitchen, drained a pot of boiled potatoes, then began to sharpen a knife on a stone, whisking it back and forth. The conure perched on her shoulder, muttering as it preened her hair. June said, “I had to quit my bookstore job to take care of him. I loved my job—talking to the customers, meeting writers. My only pleasure these days is the few minutes I can slip away and watch the birds.” She started cutting the potatoes into dice.

“Fern said you could see Kent Mercer’s house from here. That’s why I’m here, it’s the murder case I’m investigating. She said you saw Mercer having sex with your niece, Nikki.”

“She told you that? It was the day before Erwin had his stroke. He was outside bird-watching, and called me. I could tell he was disturbed—his face was white as this potato. He didn’t say a word, just handed me the binoculars and pointed across the lake to the Mercers’ house. I looked, and saw Mercer standing there naked. Wrapped around him was a woman who wasn’t his wife. I knew the wife had dark hair. This woman had long blond hair. I couldn’t watch what they were doing; it seemed so twisted, that they might be having sex outdoors, in full view of everyone. Then Erwin said, ‘It’s Nikki.’ I can still remember how sick and angry he sounded.” June contemplated her husband lying in the recliner, his mouth slack and open, his eyes glazed. Flickering light and mindless noise from TV cartoons washed over his blank face. “I could tell he wanted to go over there and beat Kent Mercer’s brains out. You know, Stella, if Erwin wasn’t so disabled now, he’d be your prime suspect. He was furious.”

“What did you decide to do about it?”

“We told Nikki’s mother, of course. And then Erwin had his stroke the next day, and I had other

things to worry about.”

“Was Erwin close to his niece?”

“Yes, very close. She always spent summers with us, and we’ve done what we could for her. We sent her clothes and toys when she was little and her mother was struggling. Even when Zoë was married to Oscar Schubert, wealthy as he was, he didn’t want a penny spent on Nikki. We paid for her braces, her bicycle, her clothes—everything. Oscar Schubert was a nasty, cheap piece of work.”

Muttering what sounded like bird-swears, the bird hopped from June’s shoulder to the table and marched around. I put my hands in my lap lest it think I had treats. “That’s Zoë’s second husband?”

“Her third. A radiologist, richer than Trump. If you want to hear about my sister-in-law, it’ll take a while.”

Ah. I remembered at Mercer’s funeral what Nikki said about her mother’s upcoming wedding—fourth time around, it better be simple and Zoë correcting her: third, you know how she exaggerates. Amusing, that Zoë had deleted one of her marriages from her history.

“Zoë and Erwin were raised in Salt Flat, Texas. Dusty, hardscrabble ranch, no money, shooting squirrels for food. Their parents worked themselves near to death, trying and failing in one harebrained scheme after another. Never enough money. I bet Zoë started looking for a way out before she was ten years old. She married Tommy Truly ’cause he had a pickup and a business. Gas station. He was a good mechanic and the two of them worked like mules. Then Nikki was born, the bills piled up, and the fights started. Zoë left. She waited tables and somehow finished nursing school. She married again—an Air Force guy—it lasted six months. He liked his pretty wife, but not the brat—Nikki’s always been a handful. That’s when Erwin started sending Nikki clothes and toys, and paying for the child to visit us.”

The bird startled me by flying onto my shoulder. June smiled. “He doesn’t take to everyone. You should be honored.” She took a head of celery from the fridge, broke off a few pieces for chopping.

“She has money now,” I said, thinking of Zoë’s Silver Hills mini-mansion.

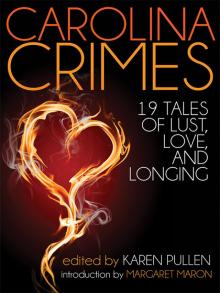

Carolina Crimes

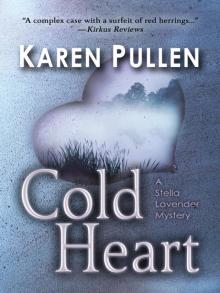

Carolina Crimes Cold Heart

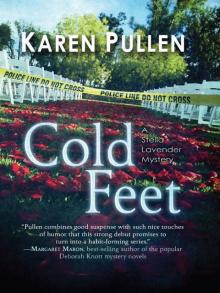

Cold Heart Cold Feet (Five Star Mystery Series)

Cold Feet (Five Star Mystery Series)