- Home

- Karen Pullen

Cold Heart Page 2

Cold Heart Read online

Page 2

The dilapidated farmhouse looked nearly abandoned, except for the climbing roses she tended carefully, entwined around trellises. The house hadn’t been painted in decades, and the rusty tin roof leaked under the eaves. The porch was hazardous, with water-rotted columns, missing balusters, and sagging steps. The farmhouse was a huge worry to me. I hated to see it deteriorate, but I couldn’t afford the new roof it needed. I took Fern’s trash to the recycling center once a week and paid a neighbor’s boy to mow the weeds.

I tapped on the back door, then pushed it open. “Fern?”

People find it odd, even mildly shocking, that I call my grandmother by her given name. I always have. In the Lavender household there were no Nanas or Mommys, only my great-grandmother, Phoebe, grandmother, Fern, my mother, Grace, and me. We all grew up in this farmhouse.

“In here,” she called. I found her in the kitchen sorting through a pile of cents-off coupons. My heart warmed at the sight of her cherubic face, framed with a white pixie cut. I leaned down and kissed her cheek. “Who was that leaving?”

“Harry Edwards.” The lawyer, as I’d suspected.

“Ah. This is recent?”

“Oh, we go way back. He made me breakfast. A lovely omelet.” Fern wore jeans and a red t-shirt, nondescript on any other sixty-two-year-old, but, with curves in all the right places, she was a man magnet. Both of us were exceedingly puzzled that I didn’t inherit that exact gene. My attractive force was more like static cling—annoying and easily peeled away. “There’s grits left, want some?” she asked.

“Not really. Just coffee.” Congealed grits in the dented saucepan, worry over this falling-down farmhouse, and the reminder that my grandmother’s love life was infinitely more exciting than mine—all combined to irritate me, a familiar feeling. I poured myself a cup and added milk.

“Can you shop for me? You can have these coupons.” She seemed to live on toast and cheese, washed down with tarry coffee. She dug around in her black satchel and pulled out a five-dollar bill. “I need tomatoes, milk, and cheddar slices—real cheese, not the cheese food you got last time.”

“I did? Sorry.” I put the money in my pocket. Five dollars might have bought Fern’s groceries twenty years ago, but I’d spend at least forty. We both knew it, and neither mentioned it.

“You have to eat. I’ll make you some eggs,” she said. She scraped butter into her cast-iron frying pan, heavy, black, seasoned to perfection. It, and the kitchen, hadn’t changed in years. Checkered linoleum had been put down around 1950. The stove was antique—not the valuable kind, but the kind with two non-working burners. Knotty-pine cupboards held everything from plain ironstone to elegant porcelain, jelly jars next to crystal.

I wondered how much longer Fern could live like this. Her only income came from the painting classes she gave and an occasional sale of one of her pieces, so I paid her bills and bought the groceries. I wanted her to sell the property and move into a convenient apartment. The ramshackle farmhouse wasn’t worth much, but sixty-eight acres on a state highway had to be valuable. Fern didn’t want to live anywhere else. She refused to sell.

She handed me a plate of eggs and toast and we gossiped about her neighbors and my job. Fern liked to hear about my work. She understood why I was a cop—she’d lost a daughter, my mother, Grace, to crime. We never admitted aloud that Grace was dead, but twenty-two years ago my mother had disappeared in a robbery-abduction. A cold case. I’d studied the case file enough times to know what happened to her would be a mystery until, some day, someone talked. Unlikely. A misery Fern and I shared.

Rain hit the tin roof, at first a patter, then a gushing downpour. Within minutes, water started dripping into a bucket placed strategically in the hallway. I sighed. I could ignore the leaks only when it wasn’t raining. I rinsed my plate. “Before I put Merle to work, show me your new painting,” I said.

Fern led the way to one of her front rooms, converted into a practical workspace. Canvases leaned against the walls; props and bespeckled drop cloths littered the floor. A regular “plop, plop, plop” into a bowl in the corner caught my attention.

“That’s a new leak,” I said. “Where’s it coming from?”

Fern ignored me. Okay, stupid question. “I mean, is there water in the upstairs front too?”

“Sort of. It’s drizzling down the wall. A trickle. Here, what do you think?” She pulled a canvas onto an easel.

In the past year, Fern’s style had toughened, the brush marks more emphatic, wider, as if she didn’t have patience for fine lines. A smudge of white for light, a swath of black for shadow, enough detail to show the subjects. This painting was a still life of my old toys—a dirty brown bear in a Cinderella crown, holding a magic wand, propped against a small rocking chair.

“Gosh, you remembered those?” I asked.

“Turn around. I dug them out of your closet upstairs.”

Brownie, along with the crown, the rocker, and the wand, lay in a heap on the floor. “They look better in the picture.”

Fern looked wistful. “I paint the memories, too. I miss that little girl. It’s yours, of course. It wouldn’t mean much to anyone else.”

I put my arms around her. “It’s a beautiful picture. Thank you. Now I have to hide some socks.”

CHAPTER 3

Monday morning

Richard was absorbed in his latest management book, Monday Morning Leadership. My boss was going to ignore me whether I stood or sat, so I might as well be comfortable, and I sank into a chair. I studied him, looking for something to appreciate, perhaps what he was wearing, like his polished wingtips or today’s crisp shirt of palest peach, a pleasing complement to his mocha-brown skin.

“I want a different assignment,” I said. “It’s dangerous out there. I feel like bait.” My stomach churned as I waited for his response. A million dust motes danced in the sunlight slicing through his window blinds, striping the flat gray carpet and my favorite shoes, red slingbacks. The heels were worn. I tapped a reminder into my phone: red heels. I’d take them to the demented shoe-repair guy in his tiny cubbyhole at the mall, who ranted under his breath about the God Damn Government as he tore shoes apart.

I empathized. I, too, felt like ranting about the God Damn Government—my employer, the State Bureau of Investigation. Richard was the SBI special agent in charge of the capital district. I was a mere special agent, in charge of very little. I hoped Richard was absorbing leadership tips from his book that would work to my advantage.

His coffeemaker puffed out clouds of rich smells. When the puffing changed to hissing, as if it were a cue, he put the book down and swiveled in his leather chair. “Fredricks tells me you’re good at undercover.”

“Does he?”

“Before that you were working with the inter-agency bunch.”

“Yup.” I’d spent three months zooming around North Carolina in a helicopter with a thermal imager, looking for indoor pot gardens and meth labs.

“How’d you like it?” This was new, Richard caring whether I liked an assignment.

“Once I got over being airsick you mean? I learned a lot.”

Richard spun again to enjoy his corner-office view of the parking lot. “You hated it, didn’t you?”

“Every bleeping minute.” I hated it from the first day—when the pilot, a state trooper twenty years my senior, grabbed my thigh, forcing me to express my need for personal space in blunt language—until the last day, when we raided a trailer full of thriving plants under gro-lights and arrested a man who wept as his four children wondered where they’d get their lunch money now. No, drug interdiction was not my favorite assignment.

He poured himself a cup of coffee and stared at me over the rim of his mug. “You’re not a team player, Stella.”

Ouch. I thought about volunteering to read last week’s book, still on his desk, Six Sigma Team Pocket Guide. “I was good on the inter-agency team, wasn’t I? I followed regulations. Were there complaints?”

“Hank di

dn’t like you.”

“The pilot? Hank liked me a lot. I had to make him not like me so much.”

Richard frowned. He hated hearing about interpersonal conflicts. “You’ve put in a lot of overtime. Take the afternoon off. Maybe you’ll feel different tomorrow.” He opened his desk drawer and took out his cigar box. He selected one, laying it on his desk in preparation for ceremonial cutting and après-lunch smoking.

“I doubt it.” I wanted to grab Monday Morning Leadership off his desk and find the page describing me: a Driver, not a Passenger; a square peg/round hole misfit.

He found a different metaphor. “I’d rather pitch to your strengths, Stella. I’ll keep you in mind for a different assignment.”

That was the first thing he’d said to me in a long time that I liked. Maybe those books were working.

I drove home, changed into jeans, and picked up Merle, planning to take him for a hike along the Rocky River. As I passed the high school, I saw a teenage girl hitchhiking. Idiot. I slowed to a stop and she got into my car, slinging a backpack onto the floor. She looked about sixteen, with small neat features, blond bangs covering her forehead, and a ponytail to the middle of her back. Silver hoops marched up her earlobes and a slim figure meant she could wear the skinny jeans I had to avoid.

“Thanks,” she said. “Women never stop.”

“Where are you going?”

“Silver Hills.” An expensive gated golf community a few miles north.

“I’ll take you there if you’ll listen to these numbers.” I was making an effort to keep calm, not throttle her for terminal stupidity. “There are almost six thousand registered sex offenders in this state. They’ve been convicted. But only one in seven men arrested for rape is convicted, and only one in twenty-five reported rapes results in an arrest. And most rapes aren’t reported.”

She closed her eyes and puffed out a breath, fluttering her bangs. “Spare me the lecture. I have to babysit, and the kid’s dad didn’t pick me up like he said he would. I waited at the school bus stop for an hour. What was I supposed to do?”

“Let me simplify. Predators look for girls like you. Girls are picked up and never seen again.”

“Yeah, yeah. What makes you so smart?”

I showed her my ID. “What’s your name?”

“Nikki Truly. You’re a cop? You’re no older than me.”

“What makes you so smart?”

She laughed, showing even white teeth, transforming her face from sullen to cute. “OK. I get it. Next time I’ll call a cab.”

The entrance to Silver Hills was blocked by a red-striped boom, a flimsy barrier between its residents and undesirables. A spiky-haired guard emerged from his hut, nodded at Nikki, and raised the boom.

“He knows you,” I said.

“I live here,” she said. Wow. What would it be like, to have parents with money? Fern, a literally starving artist, had raised me. Many’s the night she and I chowed down on oatmeal and beans, having exhausted our food stamps for the month. I drove slowly, past starter castles and baronial mansions with rock walls, each one landscaped at a price probably exceeding my salary. We passed a golf course, signs to a club house, tennis courts, a pool. “Where to?” I asked.

“The Mercers’, where I’m supposed to take care of their kid.” She directed me through hilly, curved streets into the driveway of a pink-brick two-story with a three-car garage. Compared to the houses around it, 1146 looked ill-tended. A patchy sod border encircled the house and a few small shrubs struggled in the muddy red earth of planting beds. “Come in with me,” Nikki said. “I’ll introduce you to the dad. You can give him the lecture so he won’t be late again.” I rolled down the windows, told Merle I’d be right back, and followed her to the front door.

There were no cars in the driveway but through a garage window we could see a new-looking, burgundy SUV. “That’s Kent’s car. I wonder why he didn’t pick me up,” Nikki said. She tried the front door—it was unlocked. We walked into a high-ceilinged living room. Warm sunlight, tinted green from the trees outside, reflected from polished, oak floors. Stairs curved up to a second-floor balcony. The walls were covered with photographs—pictures of faces, hands, insects, babies, animals—living things. I didn’t inherit any myself, but I recognize genuine artistic talent when I see it, and was drawn to photos of a toddler with delicate features, dark hair with straight-across bangs, hazel eyes. “This is the child who lives here?” I asked. “She’s beautiful.”

“Yeah, Paige. Her mom’s a photographer. Kent?” Nikki called. There was no answer. “I’ll see if Paige is here.” She climbed the stairs.

I wandered into the kitchen, an acre of pickled-oak cabinets and black granite, cluttered with dishes and half-eaten food. French doors were open so I stepped onto the cypress deck, where a blue umbrella offered shade to a teak table. Below, a sandy path led through white-petaled dogwoods down to the shore of Two Springs Lake. A pretty postcard scene.

But on the patio below, something unnatural caught my eye. Bare feet, muscular legs.

Unmoving, still.

I leaned over the deck railing, recoiling when I realized what I saw.

A man lay on his back, probably dead, I thought immediately, based on the puddled blood that had poured from great gaping slices running from the crook of his elbows to his wrists. Under a golden tan, his skin was waxy, bluish. His hair was crinkly blond.

What was doubly shocking, I recognized him. Last night, this man had sold me twelve hundred dollars’ worth of oxys.

In a styrofoam to-go box.

CHAPTER 4

Monday afternoon

I called nine-one-one, then took a closer look at the body. It didn’t look like a suicide because there was little blood on the man’s torso or shorts. He couldn’t cut one arm, then the other, and not get blood everywhere. Blood had spurted from the arteries in his arms onto the stones underneath, forming two distinct puddles. But there was no sign of a struggle, as though he had passively accepted his fatal injuries.

I had to tell Nikki, warning her it was a horrific scene. She leaned over the deck railing, and when she saw the man’s body, she gasped, then screamed “Kent!” over and over, so loudly they probably heard it in the next county. She started down the stairs to the patio. I pulled her back and led her, hysterical and shaking, into the house where I parked her on a sofa.

As we waited for the police, Nikki clutched a pillow, rocked, covered her face. I sat beside her, patted her back, antsy to look for evidence, but not wanting to contaminate the scene. I’d spotted smudges of blood in the kitchen and on the deck. Nikki and I had probably walked on it. It was best we disturb nothing else.

The dead man was the father who was supposed to pick her up to babysit. I was itching to quiz her, extract every single byte of information from her skull. How often was she in this house? Did she ever visit for any other reason? What kind of person was he? Did he get along with his wife? Who else took care of the baby? Did Nikki know he sold drugs? But questioning the teenager would be the investigators’ job.

She took a shuddering breath, dropped the pillow, and stood. “I have to find something.”

I had to stop her. “The police won’t want us touching anything.”

“Fuck them.” She started down a hallway and stopped at the door of an office, now trashed. Files dumped, desk drawers opened and tossed, papers, folders, and supplies strewn everywhere. I saw a keyboard and mouse, a monitor, but no computer.

“Shit!” she wailed. She turned and ran up the stairs, charging into the master bedroom, an enormous room with two walk-in closets. I trotted right behind her. When she began opening drawers, I said, “Stop. This is a crime scene.”

“You don’t understand!”

“You’ll be charged as accessory to murder if you mess with stuff. It’s bad enough your fingerprints are everywhere.”

Nikki looked at me, frowning. “Seriously?”

“Come on, let’s wait by my car.”

&nb

sp; Deflated, she followed me downstairs. When I opened the front door, there stood my favorite law enforcement officer, Anselmo Morales. His eyes squinted, like he couldn’t quite believe what he saw. “Stella?”

What could I say? We have to stop meeting like this? But it was no joke. “There’s a dead man out back, on the patio. I was giving the babysitter here a ride. Nikki Truly, this is Lt. Morales.”

We both looked at Nikki, who burst into tears again, either from grief or frustration that she couldn’t find what she wanted. Or a ploy to elicit pity, in case she was about to be arrested for tampering with evidence? Something about her seemed calculated, not so innocent.

“Officer Chamberlain will take your statement,” he said, motioning a young deputy out of his car. They spoke briefly. Chamberlain was an African-American woman with pronounced cheekbones and reddish hair cut very short. She treated a sniffling Nikki gently as she took notes, walking us through the past half hour. She asked us to stop by the law enforcement center later, to provide fingerprints for elimination purposes, then let us go.

Nikki told me she lived about a half mile away, on the other side of Silver Hills, so I offered to drive her home. She had calmed down and even greeted Merle with a pat on his head. “I have a dog,” she said, buckling her seat belt. “Tiny. He’s my mother’s, actually. He barks a lot. Bites people.”

“Really? Bites?”

She held out her thumb to show me a tiny puncture, then leaned against the door, chewing her fingernails. “I bet you see a lot of dead people,” she said. “In your work, I mean.”

“Actually, no. It’s rare. That was a terrible sight.”

“Not my first dead body. My stepdad died when I was twelve. Insulin overdose. Or painkillers. They weren’t sure which. I found his body.”

“That’s awful.” So young, to be exposed to death, then and now.

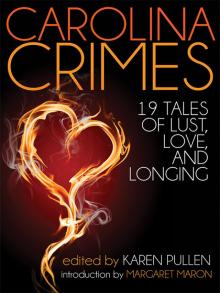

Carolina Crimes

Carolina Crimes Cold Heart

Cold Heart Cold Feet (Five Star Mystery Series)

Cold Feet (Five Star Mystery Series)